|

The Ten ‘Must-See’ Sites of

- Ancient Greece -

|

In this article we at Astarte Resources rank the ten sites of ancient Greece that we feel would be of interest to teachers and students of ancient history. In this particular article we limit ourselves to those sites found on mainland Greece. With a historical heritage as rich as one finds in Greece, any ten point list will have omissions but we’ve tried to highlight what we feel is the ‘best of the best’. See if you agree!

1. THE ATHENIAN ACROPOLIS

This site does not necessarily receive its ranking due to its location, and it certainly does not achieve it due to its serenity, but the Athenian Acropolis is one of the world’s most important archaeological sites. This is because the buildings of the Acropolis are the embodiment of Athens during the fifth century BC. They hold in trust for us a tangible memory of a time when democracy was given its first try-out, when the theatre and western science were born, when philosophers started asking the hard questions and when written history was made into an art form.

The Acropolis is a precinct containing several monuments among them the Parthenon, the Erechtheion, the Temple to Athena Nike and the monumental entrance, the Propylaia. All these constructions were completed during the fifth century – spanning a period from when the city was at the head of a maritime empire to when it was wreaked with plague and suffering grievous defeats at the hands of its enemies. Yet the building went on and the result we have today is a complete religious sanctuary of the Classical Greek Period.

|

|

|

|

A view of the Athenian Acropolis. Visible buildings on top of the Acropolis all date to the fifth century BC. In this photo the Athenian Agora (marketplace) is in the foreground.

Photo by Ben Churcher, Astarte Resources

|

|

|

2. MYCENAE

This site has been known throughout history as the legendary home of King Agamemnon who led the Greeks in the Trojan War. The story recounted by Homer shows Mycenae as a chief-city, lording it over a coalition of princely states during the Mycenaean period (1600-1100 BC). Modern scholarship tends to agree with this view and it sees the Greek Archipelago during this time being similar to feudal Europe where a group of royal families, related by kin and history, ruled much of Greece. Exactly what power Mycenae had over the other cities is a debated issue, but the impression of a dominant Mycenae is helped by the wonderfully rich finds the site has produced; many brought to light with much fanfare by none other than Heinreich “the discoverer of Troy” Schliemann himself. The shaft graves of the early kings (1550 BC) that Schliemann discovered are displayed immediately as you enter the Athens National Museum. A large room, filled with glass-sided cases, holds a beautiful array of finely crafted grave goods including the famous gold death masks. These spectacular finds show Mycenae to be the centre of a rich culture, regularly in contact with trading colonies in Syria and Cyprus. The site itself is at the head of a valley overlooking the Argos Plain and the view from the throne room can be stunning. Unlike most sites in Greece that close at the ridiculously early time of 3pm, it is open until sunset in summer. If you stay nearby, this is a great opportunity to enjoy the site practically by yourself. When you are at the site at these times you can not help but put your trust in Homer and let your imagination go – even if there’s not been a shred of evidence found linking the site to a king named Agamemnon!

Things to note when visiting

- The Lion Gate is thought to be a royal/city emblem. It is clearly based on Minoan artistic forms and several very close representations have been found etched into Minoan and Mycenaean gemstones. Two lions, their faces missing, stand either side of a Minoan downward-tapering column and an altar. It would have been seen by its makers as a way of spiritually protecting the main gate of the city.

- The walls of Mycenae are so massive that even the ancient Greeks thought they’d been constructed by gods. While the tower and gate system at Mycenae is not as classically formed as that found at the neighbouring site of Tiryns, it is impressive nonetheless. The gate at Mycenae is protected on both sides by towering walls that would have exposed an attacker to fire from all sides. For those attacking by chariot, the gate was a dead-end as there was little space to manoeuvre once inside – and an uphill slope made the attackers work hard for their prize. Although the Mycenaean royal families fell from power around 1100 BC there has been no sign of sustained warfare on the walls and citadel at Mycenae. Scholars now see the end of the Mycenaeans being brought about by a collapse in living standards that occurred right across the eastern Mediterranean at this time. The reasons for this collapse are still unclear, but at Mycenae the small elite of royals were overthrown by their own people who then continued to live in an impoverished village within the walls. By the Classical Period the walls were well-known and legendary ruins.

- The site of the shaft graves excavated by Schliemann is preserved inside the gate to the south. Here, sometimes in driving rain to try an outwit the diligent Greek representatives who did not trust him one bit, Schliemann pulled a fantastic treasure from the ground. It is amazing this treasure had survived so long for Schliemann to find. The Mycenaeans certainly knew about the graves because when they extended their defensive walls in 1350 BC they made a detour to purposefully enclose the grave area and Classical Period writers mention that the graves of the kings were inside the walls – yet no-one in all those years thought to plunder them. For this we are extremely fortunate.

|

|

A view of the famous Lion Gate at Mycenae (built 1250 BC). Beyond the gate is Grave Circle A that dates to 1550 BC. These graves yielded over 15kg of golden artefacts that are now on display in the Athens National Museum.

Photo by Ben Churcher, Astarte Resources

|

|

|

3. OLYMPIA

Famous as the home of the ancient Olympic Games, Olympia is one of the most beautiful sites in Greece, and fortunately for us, it is also well-preserved through being covered by silt from the nearby Alpheios River. From their beginning in 776 BC, the Olympic Games were held at this site almost every four years until they were banned by the Byzantine Emperor Theodosius II in AD 426.

Things to note when visiting

- The building to the west of the site, last used as a Byzantine church, was once the workshop of the great classical sculptor, Pheidias. Pheidias was responsible for overseeing the building and sculptures of the Parthenon at Athens and also the colossal statue of Zeus at Olympia – one of the seven wonders of the ancient world. In the local museum you can see his wine-cup with his name scratched on to it.

- The statue bases on your left as you enter the stadium once supported statues of Zeus paid for by those caught cheating in the games.

- The stadium appears largely as it would have looked in the fourth century BC when it was built; with grassy banks for spectators to sit on, rather than seats. The only seats belonged to the judges and to the priestess of Demeter – the only adult female allowed to attend the games.

- The premier event in the Olympic Games was the one stadia (200 m) race. In this race the runners would have started at the eastern end of the stadium and run to the west – towards the sacred temple of Zeus in whose honour the race was run.

|

|

The Temple of Hera, wife of Zeus, at Olympia. In the honour of Hera, female athletic events were also held at Olympia.

|

|

|

4. DELPHI

There is very little between the top four rankings and many travellers to Greece would place Delphi at the top of their list. On a quiet day, or on a misty morning, it is perhaps one of Greece’s most evocative sites. Located on a steep mountainside, Delphi was home to one of Greece’s most famous oracles – the Pythia. During the Archaic Period (8th-6th centuries BC) the city came to wield a lot of political power and although this influence had waned by the fifth century BC, Delphi maintained its importance as a supposedly neutral city that became, like Switzerland today, a centre for inter-city diplomatic relations.

Things to note when visiting

- The most politically important monuments are on either side of the main road just after you enter the sanctuary beyond the Roman Agora. Monuments in this area only survive as foundation stones, but if disentangled with a guide book, they represent a masterful use of propaganda – especially between Athens and the Peloponnese.

- The restored Treasury of the Athenians was more a trophy house than a treasury as we would imagine it. Adorning its walls and exterior were captured Persian weapons emphasising Athens’ role in ‘saving’ Greece during the Persian Wars.

- The temple of Apollo is a good example of a Doric-style temple – still with the outside altar largely intact (so often not present).

- At the top of the site is a well-preserved example of a Roman period stadium. Greek stadiums would not have had stone seating.

|

|

The thalos temple to Athena at Delphi. In the background is the mountain scenery that makes a visit to Delphi so memorable.

Photo by Ben Churcher, Astarte Resources

|

|

|

5. PYLOS

Excavated in 1939 by Carl Blegen (who also worked at Troy), ‘Nestor’s Palace’ is a well-preserved Mycenaean building. Named after Homer’s King Nestor of Pylos, the site is beautifully situated in the southeast of the Peloponnese. Although archaeology has not confirmed that a man named Nestor ever lived in this palace, the megaron where a king like him once resided still survives. Visitors today can walk through the palace, past the guard chambers and into the throne-room dominated by a large circular hearth. To one side are the domestic quarters, and to the other were rooms devoted to the palace’s administration. In one of these rooms were found dozens of tablets written in Mycenaean

Linear B script that provide a good picture of the local economy at the end of the Mycenaean Period (1100 BC).

Things to note when visiting

- One of the world’s oldest surviving bathtubs is situated in the so-called ‘Queen’s Quarters’.

- To the north of the throne-room is a well-preserved palace storeroom with lines of clay pithoi jars built into the bench-top.

- Although the walls are only preserved to a maximum of 1.5 metres, a staircase is visible to the east of the throne room indicating that the palace had a second floor.

- The palace’s main port can be seen in the distance at the Bay of Navarino, Pylos – also the site of a pivotal engagement during the Peloponnesian War (425 BC).

|

|

View of the Mycenaean palace of King Nestor at Pylos. The fragile remains are protected by a modern roof preserving, among other things, the ‘Queen’s Bathtub’; one of the earliest examples of such luxury in Greece.

|

|

|

6. CORINTH

Although Corinth was one of the more important cities of ancient Greece, most people visit the site today because of its association with the visit of St Paul during the Roman Period and a lot of the monuments we see today at Corinth – the forum, the lines of shops, the multi-seated latrine – date to the Roman Period. A reminder of Corinth’s early history is the massively constructed Temple of Apollo, reputedly the first stone-built Doric-style temple in Greece. Although only a few columns remain standing, there is enough of its brooding presence to remind us of what it must have been like when complete.

Things to note when visiting

- St Paul would have preached both in the forum that is within the fenced area, and at the theatre which is in a badly ruined state outside the site near the car park.

- Corinth was a renowned maritime power, yet the site is some kilometres inland. Visitors to the site must imagine parallel walls running down to the Gulf of Corinth. Here there would have been warehousing and harbour facilities.

- Behind the site to the south looms the precipitous cliffs of Acrocorinth or Upper Corinth. At the top is a ruined and overgrown medieval castle, and a superb view to the north. With this vantage point you can see the two reasons for Corinth’s success – the sweep of the sea that encouraged trade – and the narrow Isthmus of Corinth – a vital land-bridge between north and south Greece – that gave Corinth a valuable strategic asset.

|

|

The Temple of Apollo at Corinth, seen here in the background, is Greece’s earliest stone-built Doric-order temple.

|

|

|

7. VERGINA

Most of our selection falls geographically in the Athens/Peloponnese region but North Greece also has many wonderful archaeological sites. Dion beneath Mt Olympus, Amphipolis or the Australian-excavated site at Torone are all worth visits, but when looking to the north, we have settled on the royal capital of the Macedonians – Vergina. By the time of Alexander the Great Vergina had been superseded as capital by the city of Pella down the road, but it remained a ceremonial centre for the Macedonian royalty.

Things to note when visiting

- Excavations in 1977 by the Greek archaeologist Manolis Andronikos unearthed the site’s greatest treasure, the royal grave of Alexander’s father, Philip II of Macedon. Buried beneath a tumulus was a stone built tomb containing the personal effects of the king. Among these items are tiny ivory carvings of Philip and Alexander – in particular, the Alexander bust is the only known sculpture of Alexander taken during his lifetime. There were also two different sized greaves (shin-armour) in the tomb and it is well known that Philip was lame. A brilliant gold larnax (casket) contained the king’s ashes. Until recently these wonderful artefacts from the time of Alexander were on display at the Thessaloniki Museum but they have been recently moved to a purpose-built museum at the site. A recent article has argued that the tomb was in fact Alexander’s, not Philip’s, but this view has not won many adherents. A visit to Vergina should include the museum, the nearby tombs that have been opened, and at the top of the site, the beautifully situated ruins of the Macedonian kings’ palace.

|

|

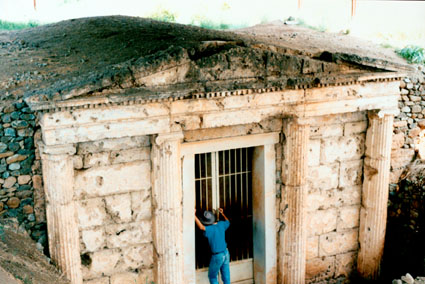

One of the Royal Tombs at Vergina (fourth century BC). Originally this structure would have been covered with a tumulus of earth.

Photo by Ben Churcher, Astarte Resources

|

|

|

8. SPARTA

The historian Thucydides predicted 2,500 years ago that there would be little left at Sparta to remind people of its greatness. And he was right! The city that was once at the head of the Peloponnesian League and home to the most feared warriors in ancient Greece is almost all gone. The Acropolis is an olive-tree covered hill with a few columns and walls in evidence and the major excavation has been to reveal the scant remains of the Temple of Artemis Orthia. There are several reasons for this. As Thucydides noted, the Spartans did not go for grand monuments and after its decline at the beginning of the fourth century BC, Sparta quickly became a provincial town whereas cities such as Athens and Corinth continued to expand and be embellished. Finally, the area around Sparta is also very waterlogged making archaeological excavation difficult.

Things to note when visiting

- The local museum at Sparta is worth a visit and it has artefacts excavated over the years on display. Among them is the famous archaic sculpture of Leonidas, the hero of Thermopylae.

- Standing in front of the football arena is a modern, but well-executed, bronze statue of a Spartan hoplite or infantryman. The statue shows the Spartan warrior in all his glory as he would have appeared in the fifth century BC.

- The one tangible link with the classical Spartan past is the Temple of Artemis Orthia where Spartan children took rites of passage that, in good Spartan style, included being flogged. \

|

|

A view over ancient Sparta from the acropolis towards the Taygetos Mountains in the west. In the foreground are the remains of a Roman period theatre.

Photo by Ben Churcher, Astarte Resources

|

|

|

9. MARATHON

Situated forty kilometres northeast of Athens, Marathon was the site of a famous battle fought in 490 BC between the Greeks and the Persians. While some might see this site’s inclusion in such a list as a bit odd as there is so little to see, it is here because of the importance of this battle – to Greece in general and to Athens in particular. In this battle 10,000 Athenian troops with the aid of 1000 troops from the town of Plataea, decisively defeated the Persians. This catapulted Athens into the limelight and was perhaps the most revered event in the city’s history. Pheidias’ Panathenaic frieze around the Parthenon is thought to have personified the 192 fallen Athenian heroes from the battle.

Things to note when visiting

- The Plain of Marathon is now covered with houses and gardens but one ancient monument certainly survives – the Athenian Tumulus – a mound raised over the Athenian dead after the battle. It stands near the point where the two armies met and excavations through the mound have revealed ash, human bone, early fifth century BC pottery and arrowheads.

- Follow the signs to the small local museum. Nearby is the smaller tumulus raised over the Plataean dead. Prior to the battle the Greeks had their camp in the hills behind the museum.

- It is also worth going down to the beach at Marathon. Here you can look to the north along the gently curving beach to where the Persians had their anchorage and stand at the spot where the Greeks battled the Persians as they retreated to their ships.

|

|

The tumulus for the Athenian dead on the Plain of Marathon. The tumulus is the original early fifth century construction while a more recent replica of the grave stele stands to the left.

Photo by Ben Churcher, Astarte Resources

|

|

|

10. THE KERAMEIKOS

Every time you use the word ‘ceramic’ you are paying homage to this site in Athens. The Kerameikos describes a district on either side of the small river Eridanos, a few kilometres from the Acropolis. From at least the Mycenaean Period until the Classical Period it was used for two purposes – as a cemetery and as a place where pottery was made (hence ‘ceramic’). Today kilns and grave monuments survive to help us visualise ancient Athenian life just outside the city wall.

Things to note when visiting

Of all Athenian sites, the Kerameikos is loaded with a variety of archaeological remains that illustrate the everyday life of Athenians from the Classical Period. For example:

- The ancient city walls of Athens cut through the Kerameikos including sections of Athens’ most ancient city wall – the Themistoclean Wall. Built into this wall were many archaic sculptural fragments from graves in the area.

- Athens’ famous Dipylon (or double) Gate is visible to visitors.

- Just inside the Dipylon Gate is a building known as the Pompeion – the place from which Athens’ major festival, the Panathenaic Festival, began.

- Issuing from the Dipylon Gate was the Sacred Way – the road which initiates for the Eleusinian Mysteries would have walked down on their way to the town of Eleusis.

- Some very good examples of classical pottery kilns survive in the south of the site.

- Many famous grave monuments Classical Period are visible.

Ben Churcher, Astarte Resources

For an examination of the highlights of Greek archaeological sites,

see our video ‘From Knossos to Athens’. Click Here.

|

|

The double Themistoclean wall running through a portion of the Kerameikos. These walls were built in 479 BC following the Persian invasions. In this view the city is to the right and the burial areas of the Kerameikos are to the left; originally outside the city walls.

|

|